Race in Cuba After the War of Independence

The black man demands no privileges: his sole desire is

to make the principles of political and social equality prevail here, and not

to be outcast from society, or to be deprived of the honor and respect he so

rightly deserves.

- Juan Gualberto Gómez

An important lesson of history is that political

leadership matters. Race and ethnicity hold strategic, not inherent or absolute

value.

- Pedro Pérez Sarduy and Jean Stubbs

During the US occupation that began at the end of the War of Independence in 1898, blacks and mulattoes were generally kept out of government as a 19th century American belief system was imposed on Cuba.

Afro-Cubans were not welcomed into post-occupation Cuba, and many considered this a direct betrayal of the ideals they had fought for. It was even suggested that Blacks had not made an equal contribution to the war, and this angered many, given that most Afro-Cubans fought in the war (82,000 Afro-Cubans died, and 26,000 whites).

In 1901, U.S. military governor Leonard Wood expressed the need to "whiten" the Cuban population. Afro-Cubans were not pleased with the apparent turn of events. They were well aware how in the U.S., the complete failure of the "reconstruction period" had led to the emergence of a disenfranchised labor class and a ruling "elite" class.

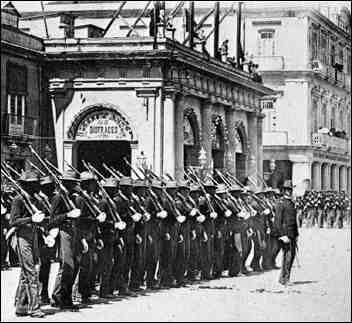

Governor Wood's attempt to create an all-white-Cuban artillery corps led to strong opposition from veteran leaders of the Liberation Army. According to Pérez, "white (Cuban) veterans made it clear that there was a blatant contradiction between the integrationism of Cuban nationalist discourse and the segregationist policy of the U.S. Government of Occupation." Wood was not always open to the Cuban point of view.

"Indeed, Afro-Cuban Mambises who had survived the war, particularly those who had served with Antonio Maceo in the western invasion, shared a deep pride and held high expectations for their future," wrote historian Aline Helg in Our Rightful Share: The Afro-Cuban Struggle for Equality, 1886-1912. "The war experience had given them a new set of references against which to measure the present. They felt no inferiority in relation to whites. They considered themselves the liberators of Cuba, who thus deserved to be rightfully rewarded after independence. To them the racial barrier seemed more unjust than ever, and they rejected the change of criteria in the assigning of responsibilities, from courage and fighting abilities in wartime to education and "merits" (according to José Martí's expression) in peacetime. Among them were the veterans Batrell, Quintín Banderas, Juan Eligio Ducasse, Isidro Acea, Evaristo Estenos, Pedro Ivonnet, Enrique Fournier, and Julián Valdés Sierra. All of these men were to play a major role in the struggle for racial equality of the 1900s, the last four as leaders of the Partido Independiente de Color."

When the first U.S. occupation ended, the Cuban government used existing racial fears to attack black organizations such as the "Partido Independiente de Color."

The Partido Independiente de Color

Along with a handful of supporters, Evaristo Estenoz and black journalist Gregorio Surín founded the "Agrupación Independiente de Color" in Havana on August 7 1908 (the name was later changed to "Partido Independiente de Color"). At the end of the month they began to publish the newspaper Previsión.

Their goal was to advocate for Afro-Cuban integration into mainstream society with equal participation in government. Their platform demanded an end to racial discrimination, equal access to education and government jobs by Afro-Cubans and an end to the ban on "non-white" immigration. Additional demands tried to improve the conditions of all Cubans: the expansion of compulsory free education from 8 to 14 years, abolition of the death penalty, establishment of an 8-hr work day and priority for Cubans in employment.

"Our motto is 'Cuba for the Cubans,'" said an editorial in Previsión on September 15 1908.

In May 1909, while serving as President of the Cuban Senate, Morúa Delgado introduced a law in the senate that banned political parties based on race or class. This was a direct attack on the Partido Independiente de Color, and was known as the Morúa Law.

Three years later a demonstration sponsored by the Independientes grew into demonstrations in which Afro-Cubans attacked and burned foreign-owned properties. The so-called "Race War" of May 1912 became a low moment in the history of race relations, and was exploited and exaggerated by conservatives and others who still dreamed of integration into the U.S.

"The movement was crushed immediately everywhere except in Oriente, especially Guantánamo region," wrote Hugh Thomas in Cuba, or The Pursuit of Freedom. "The alarm was nevertheless immense, Havana being overwhelmed by panic. Everyone had feared a 'Negro uprising' for years. The atmosphere resembled the 'Great Fear' in the French Revolution."

Race in Cuba

Opening | Introduction | End of

Slavery | Race Fear |

After the War | SUGAR | Race War |

Race War Timeline |

José Miguel

Gómez | Morúa Delgado

| Fernando Ortíz |

Julián Valdés Sierra |

Oriente Province |

Martí on Race |

Bibliography

Related:

The

Sierra Maestra |

End of Slavery |

Race War of 1912 |