Book Excerpt:

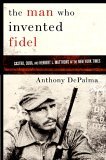

The Man Who Invented Fidel: Castro, Cuba, and

Herbert L. Matthews of the New York Times

By Anthony DePalma

Chapter 7: The Best Friend Of The Cuban People - Part 4

The Castro interview had revived Matthews's career and brought him more notoriety than he'd had since his controversial coverage of the Spanish Civil War. He developed an appetite for more adventures like it, but there was also a darker side to his escapade. He found his strength flagging. Feeling extremely worn, he consulted a doctor. Tests showed that the tuberculosis he had had as a child had come back. He had gone for a checkup in November 1956, before the first Cuba trip, and his X-rays had been clear, leading him to believe that it had been the long night spent in the damp Sierra waiting for Castro that had revived the tuberculosis after so many years. His doctor set him on a course of twenty-seven daily pills to halt the progress of the disease. He had no regrets.

"If the Cuban stories did give me TB," he wrote in a memo, "all I can say is that they were worth it to me and I would do it again."

Tuberculosis would be just one of many medical problems to complicate Matthews's later years. But because it was linked in his mind to the interview in the Sierra, he would never complain about it.

Nor did he let it interfere with his ambition to cover the turmoil in the Dominican Republic as General Rafael Trujillo's brutal regime tottered on the brink of collapse. In summer 1957, he sent a memo to Catledge and Orvil Dryfoos, making a pitch to be sent to Santo Domingo. He argued that if he were allowed to go, his notoriety would precede him and give him and, of course, the Times a competitive advantage: "The fact that I was there would be immediately known, not only in the Dominican Republic but all over the hemisphere. I think people would talk to me where they would not talk to anyone else." He tried to make the case that his dual responsibilities for the editorial board and the news desk made him a valuable resource that the Times ought to exploit, saying, "When The Times has an asset it should use it, even when that asset is abnormal and fits no hitherto accepted category. The rigid concept of a story being 'editorial' simply because it has a lot of necessary personality in it also ought to go down the drain."

The outpouring of support by the Cubans who marched in front of the Times Building was seen as evidence that he was already far too close to the story.

The response from the company president and future publisher was the first sign that Matthews's journalistic coup in Cuba could end up bringing infamy as well as fame. Dryfoos was becoming increasingly involved in newsroom affairs, an attempt to combine the business and editorial sides of the paper. "I still feel as I think we all felt yesterday-that Herbert has had enough of this," Dryfoos wrote in a memo to Robert Garst, a night editor in New York. Unlike his father-in-law, Arthur Hays Sulzberger, Dryfoos had no extraordinary allegiance or personal connection to Matthews, and he could look at the unusual arrangement with more objective eyes, realizing how great a breach of policy Matthews's double-dipping in the newsroom and on the editorial board actually was. The outpouring of support by the Cubans who marched in front of the Times Building was seen as evidence that he was already far too close to the story. And there was no appetite for having Matthews intimately involved in any other revolution. "Of course," Dryfoos went on, "if the News Department would want to send Peter Kihss or Milton Bracker [Times reporters] to the Dominican Republic that is something else again."

Matthews was disappointed, but he had little time to be discouraged. In October, the Cubans in exile conferred in Miami and signed a unity pact that brought together seven anti-Batista groups, including ex-president Prío Socarrás and his followers. Castro's 26th of July Movement was represented by Felipe Pazos and Mario Llerena, who apparently signed the document on Castro's behalf without first clearing it with him. Word of the pact reached the Sierra when a Times reporter in Washington, Edwin L. Dale, managed to break the story. Matthews, on the editorial page, considered the pact a decisive blow against Batista, representing the unification of an opposition movement that had, till then, been deeply divided. But in truth, the pact caused dissension of its own. Castro was furious. He felt betrayed by Pazos and Llerena, and marginalized by the other groups that had signed it without consulting him. His fierce reaction was also a sign of his own ambitions for power, and his reluctance to share it.

Matthews's positions in the articles he wrote under his own byline for the Times, and the unsigned editorials that were unmistakably his, had turned relentlessly critical of Batista and rarely anything but supportive of Castro and his rebels. "What we do know today, in spite of the censorship, is that Cuba is undergoing a reign of terror," Matthews wrote in October. "This is a much overworked phrase, but it is a literal truth so far as the regime of General Batista is concerned." Some of the more conservative parts of the resistance in Cuba grew worried as options narrowed and it seemed more likely that Castro, by default, had been anointed Batista's successor.

Mario Lazo, a Cuban lawyer born in the United States and cousin to respected politician Carlos Marquez Sterling, was one of the limited number of Cubans who were suspicious of Matthews. A regular reader of the Times, he had been surprised by the emotional tone of Matthews's articles and the overt stance that Matthews had taken in support of Castro. "The most reprehensible act of journalism attributed to a reputable newspaper in my lifetime," was how he later described Matthews's work in Cuba. He believed that Matthews had crossed the line of journalistic objectivity, "in effect, a journalist on a reportorial assignment assumed the posture of an insurrectionist."

As 1957 came to an end, Matthews marked the anniversary of

Castro's landing in the Granma with a laudatory editorial that further built up

the mythology around the fledgling Cuban revolution. "A year ago today one of

the strangest and most romantic episodes in Cuba's colorful history began,"

Matthews wrote. In the editorial, he reprised his own role in the myth,

breaking through the wall of Batista's censorship to tell the world that Castro

was still alive. Batista's fall was inevitable, Matthews now wrote, and

Castro's goal was simply the restoration of Cuba's democracy. He had no doubt

that Castro's forces, with the support of Cubans in cities and towns across the

island, could overthrow Batista. "Nor is there any question," Matthews wrote

with more certainty than was warranted, "of Fidel Castro becoming the next

ruler of Cuba." In the end, he bowed to the mixed opinion of Castro in some

circles. But he left no doubt about his own feelings: "Whatever one thinks of

Fidel Castro, to have survived a whole year with a small force in jungle

country against the best efforts of the whole Cuban Army and their modern

armament was an extraordinary military feat. As the second year begins there

can be no doubt that Fidel Castro has made history."

Previous | Next

From the book The Man Who Invented Fidel by Anthony DePalma. Copyright © 2006. Reprinted by arrangement with Public Affairs, a member of the Perseus Books Group. All rights reserved.

Purchase

this book at Amazon.com

Contents: Before the Revolution