The War for Cuban Independence

Intro | Before The

War | The War Begins | U.S.

Intervention | After The War |

Sidebars: Frederick Funston, American

Insurrecto | Funston meets

Gómez |

Spanish-Filipino-American War | An

Excerpt from Mark Twain |

A Poem: "Cuba Libre"

| References

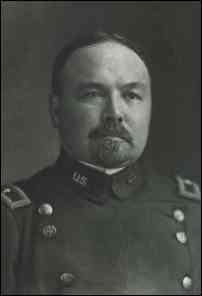

Frederick Funston, American Insurrecto

A number of Americans served in the Cuban wars for independence from the Spanish Empire, believing it to be a noble cause to risk, even give their lives to help separate Cuba from Spain. Of these, perhaps none is more colorful and respected than Frederick Funston, who joined the cause of Cuban independence in 1896 and fought in Cuba from August 1896 until about December 1897, rising to the rank of Brigadier General, and contributing to Cuban victories in Oriente as an artilleryman under General Calixto García.

Funston was born in 1865 (six months after the end of the American Civil War, in which his father served) and is remembered more for his military adventures in the Philippines, in which he's credited with the capture of Emilio Aguinaldo on March 23 1901, years after his service with the Cubans.

Funston heard first-hand account of Cuba's insurrectionary movement at a Cuban Fair in New York. Like many Americans, he'd followed stories in the papers with great interest, and was completely captivated by the plight of the Cubans. Shortly thereafter he joined the rebels, and came to Cuba in the Dauntless, a ship used to run rebel guns and supplies.

On August 16 1896 he arrived in Cuba, and on the 22nd he was at

the camp of General Maximo Gómez. His first weeks of service

coincided with Captain General Valeriano Weyler's hardening stance against the

Eastern-based insurrectos, the war had just become more harsh and

brutal, and his services were greatly needed. Funston turned out to be a

first-rate artilleryman, and his biggest problem seemed to be a common rebel

difficulty in obtaining ammunition.

Funston proved to be a good soldier who made positive contributions to rebel victories. He received various wounds, but managed to recover each time and return to the battlefield. He enjoyed the thrill of battle, but suffered a great deal of hunger along with the other Mambises. Funston liked the discipline and humanity of the rebels, particularly the practice of returning Spanish prisoners and wounded to their commanders.

As a result of his contributions to the victory at Las Tunas in August 1897, Funston was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel of the Cuban Liberation Army, one of the highest ranks obtained by a foreigner in the war. Sometime the following month Funston decided that his injuries and poor physical condition required his returning home, and he got permission from General Carlos García (Calixto's son and a friend to Funston) to leave Cuba. In spite of this, however, the civil government of Cuba at the time did not approve his request, so he went AWOL.

As he made his way to the ocean, he was captured by Spanish soldiers (December 12 1897) who did not know who he was or what rank he held. Funston pretended to cooperate by giving false information and/or information the Spaniards already knew, mixing truth with fiction and holding back anything that would hurt the rebels. He was sent to Havana, where a Spanish military tribunal believed his story and eventually set him free.

Almost immediately, Funston went to the American Consul, who originally took him for a troublemaker due to his unkempt appearance, but within a few days was on his way to New York.

Broke, tired and sick with Malaria, Funston became a minor celebrity, spending a few months in a hospital to recuperate. Afterwards he went on a lecture tour of Kansas, sharing details of his experience on the battlefield. He was a likeable speaker, and for a mere .35 cents per person, crowds delighted in hearing first hand accounts of his adventures in Cuba. "He related the background of the Ten Year War," wrote Thomas W. Crouch in A Yankee Guerrillero,* "the subsequent failure of promised Spanish reforms, the beginnings and the course of the '95 rebellion, and then a description of his own adventures. He told of his recruitment, transit, battle experiences, and personal impressions of people and places. He even included his days as a prisoner of the Spanish, for whom, to the surprise of Kansans, he had some kind words. Funston declared that the Spanish had treated him well. He said Spaniards were generally not guilty of any savagery like that committed by their loyalist allies, the Cuban guerilleros."

Funston believed the U.S. should interfere in the Cuban war for independence, since "neither side would ever quit fighting otherwise, and Cuban society and wealth would never recover from the devastation of the rebellion," if the war was allowed to continue.

* The term "Guerrillero" as used on the title of the book, is incorrect, as the "guerrilleros" were Cuban-born "volunteers" who supported Spanish rule and fought against the Cuban rebels. A more proper term for the title might have been A Yankee Insurrecto. It was the "guerrilleros" who committed the worst atrocities during the war. The use of the word, however, seems to be on purpose, given that both terms are explained thoroughly in various parts of the book.

Related:

Funston Meets Gómez |

Funston on Calixto García,

Afro-Cubans in the War of Independence