Gómez' letter

to U.S. President Grover

Cleveland

Sancti Spíritus, February 9, 1897

Mr. Grover Cleveland

President of the United States

Sir:

Permit a man whose soul is torn within him by the

contemplation of unutterable crimes to raise his voice to the supreme chief of

a people-free, cultivated, and powerful.

Do not, I beg, regard this action as an inopportune act of officialism. You yourself authorized it when you conceded to me a place in your last message to Congress.

Even more, I beg you, do not regard it as a request for intervention in our affairs. We Cubans have thrown ourselves into this war, confident in our strength. The wisdom of the American people should alone decide what course of action you should take.

I will not speak of the Cubans in arms. No; I raise my voice only in the name of unarmed Americans-victims of a frightful cruelty. I raise it in the name of weakness and of innocence sacrificed, with forgetfulness of the elementary principles of humanity and the external maxims of Christian morality-sacrificed brutally in the closing days of the nineteenth century, at the very gates of the great nation which stands so high in modern culture; sacrificed there by a decaying European monarchy, which has the sad glory of setting forth the horrors of the middle ages.

Our struggle with Spain has an aspect very interesting to that humanity of which you are so noble an exemplar, and to this aspect I wish to call your illustrious attention.

Look through the world and you will see how all people, with the possible exception of the Americans, contemplate with indifference, or with sentimental platonism, the war which makes red the beautiful fields of fertile Cuba as if it were a thing foreign to their interests and to those of modern culture; as if it were not a crime to forget in this manner the duties of social brotherhood.

But you know it is not Cuba alone; it is America, it is all Christianhood, it is all humanity, that sees itself outraged by Spain's horrible barbarity.

Well it is that the Spanish struggle with desperation, and that they are ashamed to explain the methods they employ in this war. But we know them, and we expected them.

We accept it all as a fresh sacrifice on the altar of Cuban independence.

It is logical that such should be the conduct of the nation that expelled the Jews and the Moors; that instituted and built up the terrible Inquisition; that established the tribunals of blood in the Netherlands; that annihilated the Indians and exterminated the first settlers of Cuba; that assassinated thousands of her subjects in the wars of South American independence, and that filled the cup of iniquity in the last war in Cuba.

It is natural that a people should proceed thus who, by hint of superstitious and fanatical education, and through the vicissitudes of its social and political life, have fallen into a sort of physiological deterioration, which has caused it to fall back whole centuries on the ladder of civilization.

It is not strange that such a people should proclaim murder as a system and as a means of putting down a war caused by its desires for money and power. To kill the suspect, to kill the criminal, to kill the defenseless prisoner, to kill the helpless wounded, to kill all who are able to impede its desolating action-all this is comprehensible as the way that the Spaniards have always understood and carried on warfare.

But not to pause at the holy and venerated hearth, personification of all most peaceful and noble; nor at women, emblem of weakness; nor at children, overwhelming symbol of inoffensive innocence. To bring upon these destruction, ruin and murder, constant and cruel; ah, sir, how horrible this is! The pen falls from my hand when I think of it, and I doubt at times human nature, in contemplating with my eyes dim with tears, so many hearts outraged, so many women sacrificed, so many children cruelly and uselessly destroyed by the Spanish columns.

The Spanish, unable to exercise acts of sovereignty over the interior of Cuba, have forced the peasants to concentrate in villages, where it is hoped misery will force them to serve in the armies of a Government which they abhor. Not only are these unhappy ones forced to abandon the only means by which they can live; not only are they forced to die of starvation, but they are branded as decided supporters of our arms, and against them, their wives and children, is directed a fearful and cruel persecution.

Ought such facts to be tolerated by a civilized people? Can human powers, forgetting the fundamental principles of Christian community, permit these things go on? Is it possible that civilized people will consent to the sacrifice of unarmed and defenseless men? Can the American people view with culpable indifference the slow but complete extermination of thousands of innocent Americans? No. You have declared that they can not; that such acts of barbarity ought not to be permitted nor tolerated. We see the brilliant initiative you have taken in protesting strongly against the killing of Europeans and Christians in Armenia and in China, denouncing them with evidence of heartfelt energy.

Knowing this, I today frankly and legally appeal to you, and declare that I can not completely prevent the acts of vandalism that I deplore.

It does not suffice that I protect the families of Cubans who join us, and that my troops, following the example of civilization, respect and put at immediate liberty prisoners of war, cure and restore the enemy's wounded, and prevent reprisals. It still appears that the Spaniard are amenable to no form of persuasion that is not backed up by force.

Ah, sir, the vicissitudes of this cruel struggle have caused much pain to the heart of an old and unfortunate father, but nothing has made me suffer so much as the horrors which I recite unless it is to see that you remain indifferent to them.

Say to the Spaniards that they may struggle with us and treat us as they please, but that they must respect the pacific population; that they must not outrage women nor butcher innocent children.

You have a high and beautiful precedent for such action. Read the sadly famous proclamation of the Spanish general, Balmaceda, of 1869, proclaiming, practically, the reproduction of this war, and remember the honorable and high-minded protest that the Secretary of State formulated against it.

The American people march legitimately at the head of the Western Continent, and they should no longer tolerate the cold and systematic assassination of defenseless Americans less history impute to them a participation in these atrocities.

Imitate the high example that I have indicated above. Your conduct, furthermore, will be based solidly on the Monroe doctrine, for this can not refer only to the usurpation of American territories and not to the defense of the people of America against European ambitions. It can not mean to protect American soil and leave its helpless dwellers exposed to the cruelties of a sanguinary and despotic European power. It must extend to the defense of the principles which animate modern civilization and form an integral part of the culture and life of the American people.

Crown your honorable history of statesmanship with a noble act of Christian charity. Say to Spain that murder must stop, that cruelty must cease, and put the stamp of your authority on what you say. Thousands of hearts will call down eternal benedictions on your memory, and God, the supremely merciful, will see in it the most meritorious work of your entire life.

I am, your humble servant,

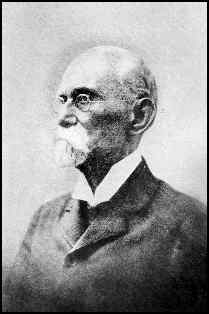

Máximo Gómez

Return to Timetable - 1897

Related:

Ten Year War | Little War | War for

Independence | Antonio

Maceo