1960: New Year's Eve in the Habana-Libre Hotel

An excerpt from the book:

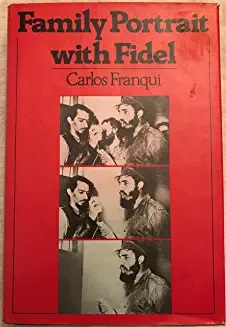

Family Portrait with Fidel

by Carlos Franqui

Random House, New York

Page 65

To bid farewell to 1959 and to greet the new and, as we would soon see, decisive 1960, we had an official dinner in the Habana-Libre. The mix at our table was a bit odd: Fidel, Celia, my wife, Margot, and I. Then two guests of "Revolución," Giselle Halimi and Claude Faux, French writes and lawyers, friends of Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, who would themselves soon visit the island. And Joe Louis, the American mulatto who had knocked out the Aryan great white hope, Max Schmeling, was Fidel Castro's personal guest. Louis wasn't scarred or physically smashed up; he was mentally beaten, punchy. I was a fan of his and remembered the party we had in my hometown with the blacks when he beat Schmeling. But what Louis meant as a symbol wasn't lost on me: Fidel was warning me again. For him, sports were more important than culture. Back in the Sierra, Fidel had wanted us to broadcast scenes from the war on Radio Rebelde while Che and I insisted on reading poetry. I remembered that on our trips to New York and Washington Fidel had refused to go to art museums, preferring to have his picture taken in the zoo. I remembered when he refused to support our petition to have the Cintas painting collection sent to Cuba. But, for all that, we still had room to maneuver, and "Revolución" still retained some autonomy. "Lunes," the Monday literary supplement edited by Guillermo Cabrera Infante, annoyed some but impressed everyone.

We were preparing for important visits: Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Pablo Neruda, and others. We wanted to bring culture to the people. Fidel didn't see things that way, but he took advantage of the propaganda. Nineteen fifty-nine had been a year of experiments, discoveries, and conflicts, a strange mixture of the old and the new, of collective justice mixed with individual injustice. Nineteen sixty would be the final test. It didn't look bad. There was a balance of power. On one side, "Revolución," "Lunes," the intellectuals, television, the students, the unions, and the old underground groups. On the other, Raúl, Ramiro Valdés, the army, the Communists, the government, Che. And Fidel above us all. The United States seemed to be setting up an attack, and the bourgeoisie, the landowners, the Catholic Church, and the politicos were emigrating. The bourgeoisie still had control of the press and the economy in cities, but the revolution held the country. Still, nothing was clear either for them or for us. The future, reform or revolution, would be determined by the position the United States would adopt, not by Fidel's desires. I personally wasn't concerned about he U.S. reaction because I already knew it would be one of outrage, but I was worried about the pro-Soviet backlash that would take place in Cuba and the possibility that Fidel would ally himself totally with the Soviet Union if there was a break with the Untied States. Many of us saw the perils built into the Soviet bureaucratic structure, which blends so easily with the militarism and caudillismo of a man like Fidel Castro. At the moment, however, the people were still armed as militia, so anything was possible, even a humanistic revolution that could be profound, democratic, respectful of civil rights, and where the people would be the actors instead of the spectators.

Return to 1960